By Henry Gboluma

KPAYEAKWELLEH TOWN, Gbarpolu-In the remote Guo Nwolaila District of Gbarpolu County, a striking reality unfolds for pregnant women, marked by resilience amid overwhelming challenges. It is a situation of accepting what is available in the face of daunting healthcare barriers.

With a population nearing 30,000, and only one clinic to serve them, accessing essential healthcare services is a daily struggle. In February 2025 alone, the clinic saw 245 female patients, many of whom were pregnant or new mothers. In contrast, male patient intake for the same month recorded just 73, according to the clinic’s attendance records. Yet, the path to receiving care remains fraught with obstacles.

“I took about five hours to come here,” shares Jocquelle Gartee, a 44-year-old mother of four, who often must ask for lodging just to wait for her delivery time. “There is no place for us to stay. We need more support from the government. We have children to feed, and we cannot afford the medicine.” Her words echo the plight of many women in the district, where lack of infrastructure and resources make access to healthcare a perilous journey.

Esther Natquine, another mother of four, expresses her frustration: “I walk an hour and 30 minutes to get to the clinic. The health workers are doing their best, but we need more clinics in Guo Nwolaila District. The only clinic we have can only give us paper to go to the market for medicine.” Her sentiment highlights a critical gap—while the clinic provides some care, the demand far exceeds its capacity.

The journey to the clinic is not only physically taxing but also a source of anxiety. Fifteen-year-old Noah Kolleh recounts her experience: “I walk two hours to the clinic, and I often feel weak. This is the only clinic we have, and we come every Thursday for treatment. Sometimes, they tell us to come back because there is no medicine.” Such accounts reveal the dire need for consistent supplies and improved access to healthcare.

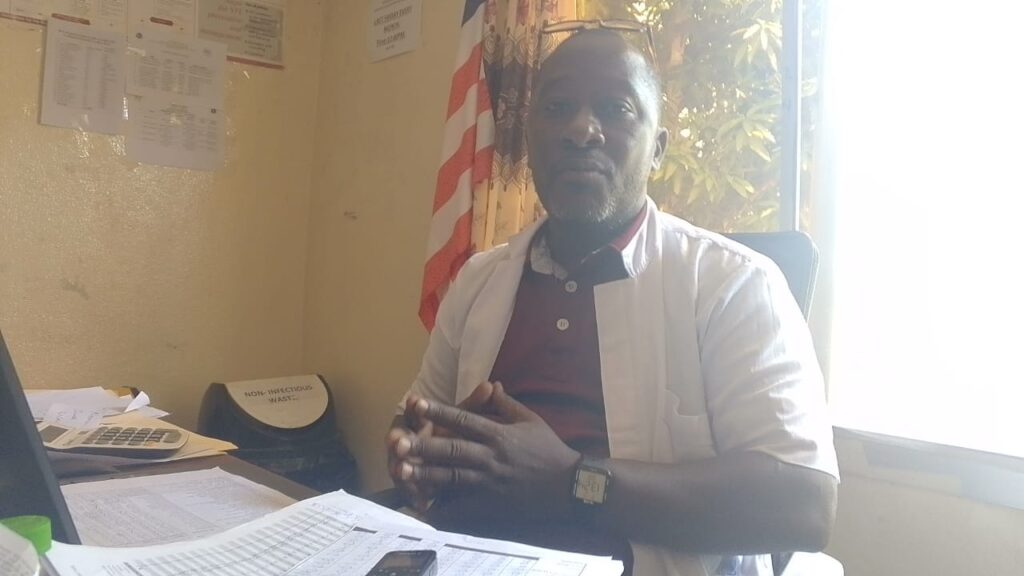

Brima D. Koroma, the Officer in Charge at the Kpayeakwelleh Clinic, paints a bleak picture of the healthcare landscape. “We don’t have any car roads. Transferring pregnant women is an immense challenge. We rely on canoes and foot travel, and sometimes we need to wait for an ambulance from Bong County.” The absence of proper transportation not only hinders access but also compromises the health and safety of expectant mothers.

Moreover, Brima emphasizes the urgent need for a Maternity Waiting Home, a facility that would allow pregnant women to stay close to the clinic during the critical weeks leading up to delivery. “For you to keep them here up to their delivery is very hard. We need a space where pregnant women can be cared for during their final months,” he insists.

Despite these challenges, there is a glimmer of hope. Brima notes that community awareness campaigns have begun to encourage women to utilize the clinic’s services. “With the support of organizations like Christian Aid and the World Bank, we are slowly improving our services. But we need more help—more clinics, better transportation, and a maternity waiting home,” he urges.

The resilience of women like Jocquelle, Esther, and Noah is commendable, yet it underscores a critical need for immediate support and intervention, according to civil society actor Lydia Ballah. Recently visiting the district, she stated that the stories of Guo Nwolaila District women are not just personal struggles; they reflect a systemic issue that demands sustained attention from lawmakers, health authorities, and humanitarian organizations.

“This is the time to act now,” Lydia emphasizes. “Not just the women of Guo Nwolaila District, but all women in Liberia deserve a healthcare system that meets their needs, ensuring that every mother can access the care she requires without treacherous journeys or undue hardship.”

“We cannot wait any longer,” Jocquelle pleads. “Our lives and the lives of our children depend on it.”

As Lydia Ballah urges, and as the world watches, let us not turn a blind eye to the silent suffering in one of Liberia’s remotest districts. With scarce resources, now is the time to invest in healthcare infrastructure, support maternal health initiatives, and provide the resources necessary to uplift these resilient women and their families.

3 Comments

Thank you for your sharing. I am worried that I lack creative ideas. It is your article that makes me full of hope. Thank you. But, I have a question, can you help me?

Thank you for your sharing. I am worried that I lack creative ideas. It is your article that makes me full of hope. Thank you. But, I have a question, can you help me? https://www.binance.com/register?ref=IHJUI7TF

Can you be more specific about the content of your article? After reading it, I still have some doubts. Hope you can help me. https://www.binance.com/sk/register?ref=WKAGBF7Y